IN CONVERSATION

Richard Baker with John Yau

A week before the opening reception of a new body of paintings at Tibor De Nagy Gallery, Richard Baker welcomed Art Editor John Yau to his DUMBO studio to view the works, and to talk about the painter's work.

John Yau (Rail): The earliest works of yours that I have seen are on a wall in the house of Pat de Groot, a painter who lives in Provincetown. They're small paintings of things—insects and fish, for example. I feel that your interest in the material world has been a driving force in your work since the beginning, but that there is nothing particularly exalted about the things you focus on, nor are you being ironic.

Richard Baker: Right, they are things that are underfoot. There is nothing extraordinarily special about them—no fantastically beautiful and rare orchid. I am interested in the daily stuff of life. And those paintings at Pat's function as icons of those daily moments.

Rail: The other thing I thought about is that your interest in things led you to become involved in still-life. Though, to broaden it, you bring in other genres, like landscape and portraiture, often, in the latter case, by painting portrait photographs and reproductions. In addition to these representations, you also paint reproductions of the senses, an ear, eye, or nose—artifacts that might be derived from a lesson teaching someone how to draw. As I see it, still-life becomes the way you engage with the history of painting.

Baker: Well, I never set out to be a still-life painter. It's not something I chose to be. Matter of fact, I found myself early on feeling shocked and nearly embarrassed that, wait a second, I'm a still-life painter—how'd that happen? So if I was going to embrace that genre, which I did, I effectively had to elbow out the edges of it. Take the things that are banished from it and try and have them re-enter the picture.

Rail: And there is the formal element because within your paintings is the constant examination of the relationship of things to the picture plane. You are painting flat things—books, photographs, and reproductions, for example—that are "placed" on a severely tilted plane. The surface of this plane—a table—is tilted in a very precarious way. It occurs to me that your work shares something with the paintings of Yvonne Jacquette, their aerial perspective. In both your work and hers, you feel like the world is slipping away just as you're trying to grasp it. Seeing is not fixed, but fluid. In your paintings I feel that the world is at once fulsome and material and it's sliding off the picture plane.

Baker: Which is true. That's the condition of life. Every moment that you're living becomes the past the moment it is lived.

Rail: And you want to acknowledge that in your work?

Baker: Right, and also by tipping the things up toward the picture plane, it is a way of acknowledging that the painting itself is an object. I am not only presenting things within the picture frame; I am presenting them on the picture plane to the viewer in a very direct way. You don't scan across the plane, its space. Rather, you look directly at that plane.

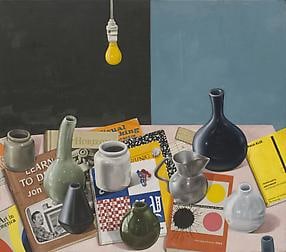

Rail: It takes a while to sort everything out. In the painting Tussle, the table is pressed up against the picture plane, but the angle at which you depict the things on it warp or bend the table's plane back in space. It takes time to see that the painting is made up of three rectangles, with the largest one being the table, and the two smaller ones dividing the upper part of the painting are a wall and an open window (or sky) with a shade's tasseled cord dangling down. They are also pressed up against the picture plane so that the table and wall behind it are both upright. There's a lot to sort it out in your mind, which echoes a still-life; it is a bunch of things strewn or arranged on a table that need to be visually sorted out. In your work, there's a direct interaction with the things—we both see and in a sense feel our way through them.

Baker: It's important for me that I do have a dialogue with the viewer. We have talked about Duchamp before and his belief that the audience completes the work of art. If I don't in some way force the viewer to be actively involved, then I'm just simply presenting something in a kind of dismissible way. I have to construct something that you get, but that deconstructs itself as you wander through it.

Rail: Well, it's interesting that you mention Duchamp as one of your influences. People might be inclined to say about you, "Oh, he's a still-life painter, how can he like Duchamp." And you're saying, "Oh, that's not the story."

Baker: Right, right. But that's the thing that's kind of slippery about painting, these sorts of paintings. I am speaking about still-life. Ambitious contemporary painting isn't supposed to engage with things like beautiful flowers. The still-life genre is not exactly the most elevated, ambitious way to paint these things. If I'm going to venture to do that, I can't simply use still-life, its history, as my only model. I have to think about many different ways of being creative and being actively involved with the whole history of art. Duchamp is definitely one model.

Rail: And he had a strong interest in things as well. It's not like he made invisible works. And this interest in things, and their identity, runs through all of his work.

Baker: Yes, from the early chocolate grinder on.

Rail: The other thing I wanted to talk about is that when you do a still-life, you are evoking our historical time. In this painting, for example, one sees copies of the New York Times and New York Post; they are upside down, and there's a blue vase of tulips resting on them. The headlines have to do with the moment the economy collapsed. So one reads your paintings, as well as sees them. But you are neither a diarist nor a symbolist.

Baker: I would try to resist the symbols. If something is overtly symbolic, I would question if I actually want it to remain that way. I am seeking a tension between the ability to read something and the inability to read something, between legibility and confusion. I'm doing a talk in a couple of weeks about representations of cloth in painting. For me, the interesting thing is that cloth both reveals and conceals. So, in terms of symbols, if something is going to have a symbolic weight, it has to both reveal and conceal. In my paintings of blank index cards and pieces of paper, the paint itself denies the ability to put a message on it. So there's a way of being clear and also of being confused.

Rail: You're thinking about painting philosophically, as an instrument of inquiry. Painting becomes a way for you to investigate the material world that you inhabit, are part of. You seem to ask yourself, why do I have affection for these things? And you also allude to certain markers of collective experience for those born during a certain era. Where do many of us see our first nude? Well, in Tussle, you place the magazine Playboy pretty much in the center of the painting, as well as cover parts of it up with other things. There are representations of all different kinds of nudes—the classical image, the photograph of the nude, and the cover of the Tom Wesselmann catalog. Where does anyone find out about the body?

Baker: It certainly shouldn't be in still-life painting. When you're talking about the body in a still life painting, isn't that unusual? Usually any kind of a conversation about a body in a still life painting has to do with the implied use a body has for the objects depicted. This is the territory that I am trying to explore—where there are the representations of nudes and figures and what not in a still-life painting.

Rail: It seems to me that one current running through your philosophical inquiry is: what is the nature of still-life. We have discussed this before when talking about the book, The Not-So-Still Life, which covers a century of California painting and sculpture. It has been said of certain artists that they ask, what's an abstract painting? I feel like you have this parallel ambition, like I'm going to take this genre that's considered outmoded and explore it. If, in Minimalist abstraction, the artist addressed the form in order to arrive at the subject, it could be said that you explore the subject—things—in order to arrive at the form, which is still-life. And, in contrast to Gerhard Richter's candles and Andy Warhol's skulls on the table, you take out the quotation marks because you want to have a direct engagement.

Baker: I'm glad to hear you say that. I've been working within this genre for several decades now and if I wasn't engaged in that way, it'd be completely dead art.

Rail: Another set of paintings that you do—well, they are often paintings on paper—focuses on paperback books.

Baker: Well, the book itself becomes a mental trigger. It triggers associations. Just by holding it you can remember when you encountered this thing. Just by looking at the cover you get this whole sense experience. You might remember the room where you first read such and such an edition of some book. The season, whatever it is. So the book itself, like other objects call up experiences, represents so much more than just its content.

Rail: Another thought I had about your work has to do with a painting you did of a porcelain bowl of fruit, which was shown a few years ago.

Baker: There was another level of remove from the actual surface.

Rail: So your interest in things extends to their surfaces. Your work is not made up of images the way it is in a Richter or Warhol still-life. You are interested in things in part because you too are a thing living with and among them.

Baker: We are bodies that apprehend these things through our senses, through touch, smell, sight, even through hearing, and as a painter, I mean I could be a photographer, and I'd eliminate that sort of experience. The porcelain—I mean somebody made this thing in the world. And then, as a painter, I apply colored mud and make another representation. I

have to be concerned with the sheen of light, the matte surface, the density of the object. I have to try to represent all of it with this oily colored mud and that's part of being a living, breathing, feeling being.

Rail: And it's also about depicting a porcelain vase out of colored mud. Porcelain was a kind of mud at one point. There's dialogue there. You are taking the porcelain object and pulling it back to a slightly earlier stage of its existence.

Baker: Now you're making it sound like alchemy.

Rail: Well, I don't think of you as being interested in alchemy in the sense of turning something into gold, or into something purer. My sense of your paintings is that you're not interested in elevating things into a purer state. You really want to deal with it in its physical, material state, as it is.

Baker: Well it's always a mess. I think you're right, I'm not trying for anything pure.

Rail: I mean you have done this still-life of a wire basket full of broken glasses. You don't know why they're broken or why they've been collected. There's no narrative and you don't try to give a clue to one. It's a collection of broken stuff. A still-life of broken, transparent things is unusual. It's not a depiction of trophies, of rare things. Also, there is the touch that we associate with Manet's late paintings of flowers and those of Richard Diebenkorn—that emotional touch. You're not using the paint itself to be emotional. You're interested in hard contours.

Baker: I've become interested in hard contours. I was once more interested in the brushstroke. Not necessarily a fluid brushstroke like Manet's, a more coarse brushstroke, but nonetheless one where we can see the brush is dragging in the paint. I was certainly interested in creating a painting that showed the mark of the hand making the image, but I've become, not less interested in it necessarily. I would say that I have moved to the opposite end of the spectrum of what paint can do and the hard contour is where I find myself. I think you mentioned before that the painting of the tulips and newspapers (Black and White and Re(ad) all Over), has a more open quality to it, that it has hard contours and also shows where I made changes, scraped paint away. It seems that I do want to go back to that other end of the spectrum at some point.

Rail: Well, it seems like you want to do both.

Baker: I do want to keep both.

Rail: You want to have the hard contour, but you also want to have the sense of something that existed in time, and was made in time, so that you see the trace of earlier views in the painting.

Baker: And time, you know, how do you keep traces of time without being heavy handed about it? There are ways other painters have registered time in a very overt way. I want to be ambivalent about it, not actually taking anything on directly and emphatically. I want things to push on each other from opposite directions.

Rail: So you're not so willing to become conclusive, to announce yourself as a conclusive being who knows this is the way it is.

Baker: I guess that's a better way to put it. I'm trying to think of a way to resurrect the word ambivalent in a more reverential sort of way.

Rail: Well, it's ambivalent in the sense that you want to know the way things are, but you're not willing to say, "This is the way things are!" You're trying to say—maybe, could it be, how is it? Recently, I've been thinking about how, in theorizing about painting, one of the things that Clement Greenberg never addresses is the constant pressure of time on the individual making the work, that time exerts a kind of constant pressure on you. He believed that painting could achieve a sort of timeless present, that instant where it is seen all at once.

Baker: Well, there was that whole notion of the frozen performance, where a series of motions by the painter got frozen on the surface.

Rail: And it becomes timeless. And that seems to me to be an illusion about life, that you can reach a moment of timelessness, because really you can't. You're always stuck in time and there's no way out. So in your painting of broken glasses, you seem to be acknowledging that chaos is always there, that things do fall apart, and that nothing is perfect. And I think that that becomes another element of meaning in the work.

Baker: Are you saying that it's acknowledging that this too shall pass, that it doesn't last forever?

Rail: Yeah.

Baker: It's like a memory.

Rail: It's not overt, it's not dramatized. Years ago, there was a painter, Helene Aylon, who did paintings that constantly changed because the combination of materials was unstable; it was a simplistic idea about time always changing, which is different than passing.

Baker: In her work, it sounds like you can connect the dots easily. I don't want people to be able to easily connect the dots. Despite that initial seduction of oh this could be beautiful or oh it's a pretty still life, I want the viewer to be actively engaged not in connecting the dots A to B to C, but to do it in a more fluid way.

Rail: Well, think about the copy of Salinger's Franny and Zooey that you put in the painting. You mentioned that you hadn't read the book in a long time, and that you found this really early copy of it, the beautiful Penguin edition, and you decided to put it in the painting. And you also put in a glass of milk. And then when you reread the book, you came across the scene where Franny's drinking a glass of milk. You could say it's a chance encounter, but it has meaning. Some people think of Lautreamont's idea of the chance encounter of a sewing machine and umbrella on an operating table as having no meaning, but, in fact, there is meaning to that chance encounter.

Baker: We're always trying to make everything into something meaningful. No narrative, no set of symbols actually has meaning until we give it meaning. In a sense, it's all a chance encounter. We happen to lie about our days. We organize them so that each event follows another event to make a meaningful day.

Rail: Let's go back to that. There's the obvious painting that deals with a received language where you can connect the dots. Still-life as a genre is thought of as something that became encrusted with dot connecting and you decided, or you entered into this situation saying, how do I open it up? How do I push it away so that there's still something going on in the painting?

Baker: Best case scenario—that is exactly what I desire, something more philosophical, something open to inquiry. It's not that the skull simply represents death and mortality, that sort of thing.

Rail: Can you open it back up? Can you take the old story and make it not a story anymore but an experience?

Baker: Norman Bryson said that one of the things that makes still-life different from all other paintings is that it banished narrative, but what you're saying is that that's not true, that a lot of still-life does embody the narrative in that you can connect the dots.

Rail: Well, the other side of your paintings, which we have touched on earlier, is that there are often books in them, particularly monographs. In Tussle, you have a comic book, a classical reproduction, an issue of Playboy, a photo of a nude, a face, and an eye, which seems to be about looking. It's a painting that comments on itself and how it emerged into existence.

Baker: With that eye, it also becomes a painting that looks at the viewer who's looking at the painting. There's a tautology.

Rail: In the familiar relationship between still-life and viewer, we look at the painting, but it doesn't look back. You've inverted it. You're getting the still-life to look back, like Manet's Olympia.

Baker: In that way it's an invitation, it becomes a conversation. Ideally.

Rail: Ideally? Well, we try to live ideally sometimes. [Laughs.]

Baker: Well, if you can't do it in painting, where can you do it? By mentioning that, mentioning the artist and how we first might encounter a new artist before going to a museum. In an essay, you pointed out that there are comic books and, in another painting, there are children's books. In a sense you hit on something where all the things have to do with a kind of a first encounter—with early education, early exposure, kind of fundamentals—where at the same time, it's a little bit backwards in the same way that the debris beneath your feet is kind of fundamental, even though it's at the end of its cycle, its usefulness has been cast aside. The random unordered world is our entry point and then we're given texts, we're given guidance out of that chaos.

Rail: In that sense, you're trying to go back to ask, where did we begin, where did my notion or anybody's notion of the world we live in begin? As you say, it's underfoot and chaotic and we encounter texts that help guide us through that chaos and for you the guides include children's books, art books, the newspaper, novels and poetry, things easily gotten. But no bible, so to speak.

Baker: Well, there are no essential texts. There are many texts, examples, and teachers, so to speak. Wouldn't it be easy if there was one system that worked for all, and for everything?

Rail: So you're saying that there are many texts and that you're also trying to discover the contours of your own limits, the hard contour that you might not be able to go beyond? At the same time, there's the open-ended side of what you want in painting. I don't know what the studio practice is inside your head, but there must be that notion of yes/no every now and then. The writer Ronald Sukenick once said to me that you become a writer at the moment when you say, oh, I can't put that in the piece and then you put it in.

Baker: That's a really good point. It makes me think of something that a writer said about Richter, he was quoting Novalis and I'm paraphrasing this badly, "man will never achieve any great representation, if he represents nothing further than his own experience, his favorite themes and objects, if he cannot bring himself to study vigilantly an object which is quite alien and uninteresting to him. The artist who represents must have the ability to represent everything." You should be able to paint things that you want to paint, but you should also be able to paint things that you don't want to paint. I keep a box of images. If I have a response to an image, I immediately banish the desire to figure out why I'm attracted to the image. It could be the color, it could be a narrative, it could be the form, it doesn't matter, I just clip it out and I put it in a box. There are things in that box that I've repeatedly said no to, but they're in this battery pack where someday that no may change to a yes.

Also, because we are talking about exploring one's limits, I have to say that part of the physical pleasure of painting is to explore the limits of what is possible in paint. You know, is it possible to render the feeling of flesh, the sheen of the ceramic, whatever it is, and so objects in the painting force me into the pleasure or agony of figuring out my own limits.

Rail: There's a wonderful poem by John Ashbery, "Daffy Duck in Hollywood," where Daffy complains about that mean old cartoonist reneging on his promise to get him out of the cartoon; it's the poem talking back to the poet. How do you subvert or undermine your own intention? While you are the maker of this, you also try and go beyond your own contours. Painting tests your limits; can I paint the shine of that porcelain? Can I put this in the painting? The painting is an instrument of inquiry, but ideally the questioning goes in two directions, toward you and toward the painting. It seems to me you do keep trying to paint different things and you have to try and figure out how to paint them.

Baker: I used to deny myself the pleasure of that

Rail: You mean you were a Puritan at one point? [Laughs.]

Baker: I think so. You know there was pressure, I think, to be clear. When I was younger I felt that it was incumbent upon me as the sole maker of this work to be clear, to know what I was saying, to know what I was providing for the viewer's experience and in that I was able to embrace the full spectrum of my abilities. I would never allow myself to do any of the kind of smooth rendering that I do in passages of paintings now, and that's one of the pleasures of painting—to paint coarsely, to paint like impasto, to paint with glazes. There's a full range, and I denied myself that full range early on under what I felt to be a cultural pressure to be totally in control.

Rail: Well, there's the painting from your last show of paintings that is based on things you found when a relative died.

Baker: Yeah, my uncle's interest in pornography. Yeah, I included many of the things that were his and they were very time-based. There was this idea that there was going be an element of nostalgia, but not at all. There definitely was a discomfort in presenting those things. It was a story that was not to be told. These are beginning to sound narrative, but hopefully it's a narrative beyond a simple story line.

Rail: Well I didn't go, oh, that's his weird uncle Ralph! The collection of things, and their visual arrangement, intrigued me. I think it's very real and human to stick a Playboy in a painting, and not be ironic or embarrassed about it. After all, where did we first see a nude? I think there's that side of your work that I find really interesting—through the genre of still-life you are asking, what can a painting say? What can it disclose and, as you say, cover over?

Baker: I find that still-life has become a really important vehicle for asking that question—what can a painting say, you know, its more than just a still-life. I just find that working within that genre and making those limits bulge at the seams, I find that it's really capable of exploring the answers to that question. Speaking of the embarrassment factor, you know, what can be more embarrassing for a young painter? It's not the Playboy and the pornography—that's almost quaint by comparison to painting flowers. I can almost be courageously BOLD about declaring that as a subject matter, especially in today's climate, but to paint pretty flowers when you're a young man, that's really dangerously embarrassing. How could I proudly say that I am an ambitious painter and paint flowers?

Rail: Well, not only are they pretty flowers, they're also ordinary ones. They're never orchids or anemones. They're tulips, you can buy them on every corner in New York City.

Baker: Exactly, exactly. Back to the debris concept, you have things that are readily at hand and being readily at hand they're also the quintessential example—the tulip is representative of the idea "flower".

Rail: In terms of poetry, you have included books by William Carlos Williams in your work. And I think there's a deep connection between you and Williams. Going back to Dutch painting, as you said, people collected certain things and asked a painter to paint them. And these books happen to be among the things that you collected, you know, or gathered together.

Baker: Or that collected me. I mean, we are the product of the things that we encounter—things that are presented to us or that we just bump into. We are accumulations of things and notions and desires and whatnot. It's funny, when you mentioned William Carlos Williams, I also thought of Creeley, but Creeley presents a different angle of that, you know, cutting down to the bare bones.

Rail: And you've put his work in yours?

Baker: Exactly.

Rail: And all of these books, it's also really the book covers. It's really you knowing a huge amount about book design and designers. There's a deep affection you have for certain book covers and the way, like you said, yeah it was the Franny and Zooey, the Penguin edition, you know.

Baker: Right, right. I have this, going back to the senses, I mean I have, you know, there's good design and there's bad design. There are things that really catch your eye. It's different for everyone. I was talking to somebody, I guess about a year ago who, you know I'm talking about these great books and certain editions and he was maybe ten years younger than I am and the books for him were totally different editions but he had that same visceral response to his covers that I had to mine—a certain kind of design that we had become familiar with, that we appreciate. I love what designers do with books—they get your attention.

Rail: Yeah, they do, don't they?

Baker: Yeah, it brings back, again, not just the content of this object, the book or the record but the whole period where you interacted with it, who you were at that time in your life—

Rail: The playing cards, do you see that as a sign of chance?

Baker: There's the potential of that but it's also the agent of gaming, so chance is an element of that. It's potential—it's like books.

Rail: Yeah, you want the viewer, any viewer, to apprehend your painting and then however they read it depends on the viewer. What he or she brings to the table, so to speak.

Baker: Exactly. And if they don't have a whole lot to bring to the table, they have enough. It doesn't have to be from on high, you know, if a Cezanne reference is even in there, you don't have to get it. You know you don't have to get every stupid pun that might be hidden in the painting.

Rail: But you do have lots of stupid puns hidden in your paintings.

Baker: Sure, sure.

Rail: [Laughter] Okay, let's get that on the table.

Baker: And, again, stupid puns have a huge embarrassment factor. I mean how many times do you sit at a dinner table and venture really awkward stupid puns that make sense and what you get is a bunch of groans–

Rail: Yeah yeah, William T. Wiley talked to me about that in terms of his own work and all the language things that he put in there; and there is anti-social factor. I think there's a kind of posed embarrassment that certain artists take and then there's real embarrassment, the anarchic, disruptive gesture.

Baker: If you venture the small pleasures of a visual pun and they happen to be embarrassing, you know, you've exposed yourself in a sense.

Rail: So it's a lot about exposure.

Baker: Concealment and exposure.

Rail: So you could say one of the things that you're interested in is the edge between concealment and exposure.

Baker: The inbetween-ness of those two things. This reminds me of a Winnicott statement, I don't know how it relates to this but it does, that it's a joy to be hidden but a disaster not to be found.

Rail: What we haven't talked about is the ways that a painting of yours can be read. There's the still-life element in Tussle, but then the things have their own dialogues and some of them are pretty hilarious. One of the things is the little cup of marshmallows placed beneath this woman's breast, the reproduction of the woman's butt and then just to the right of it, these nipples on the Wesselmann cover. Just visually, in terms of their size and contour, the nipples resemble the marshmallows and the chocolate above it. So that you read the painting, as you said, tactilely. You don't just read it as images; you literally have to read it as things.

Baker: Right, so not only is it a visual pun, but it could be called a haptic pun, that the associations aren't simply through the eye, but they're what other senses the eye calls up so that the weight and the, what would you call that, the density of marshmallow has a certain consistency that's almost flesh like. So it's a pun or an association that's not simply through the eye, but through the eye to other senses.

Rail: Right, and that's something that you made clear in your work by including images of the other senses, the eyes or, in other paintings, the ear, the nose. You want us to be aware of ourselves looking through our body as well as through our eyes—calling up all the other senses in order to engage with the painting. Something that Jasper Johns or Magritte have also done. You know, painting isn't only about the eyes, it's about our whole body as well as our mind.

Baker: Right. A sad state of affairs it would be if we were only a mind. You know?

Rail: Right, or only an eye.

Baker: The slippery relationship of those elements is what makes things pretty exciting.

Rail: It just occurred to me that you have low-grade food in your paintings.

Baker: Right, it's like the candy variety of tulip.

Rail: When I mentioned Williams and Creeley, poets of domesticity and their immediate surroundings, it occurred to me that this is something that you share with Catherine Murphy, her paintings of wallpaper, bathroom sink with hair in it, or striped comforter, for example. Two cans of ale, the front rim of a bathtub and faucets, a wicker basket—Johns' things are not exotic or elevated either. It seems to me that you are making a painting of commonplace things that show the wear and tear of life, and this is the opposite of kitsch and on the opposite end of the spectrum from irony. At the same time, it is a painting of domesticity, of the things that are underfoot in a domestic situation. The stuff of life.

Baker: Which is why they're not elitist.

Read more:

http://www.brooklynrail.org/2010/02/art/richard-baker-with-john-yau