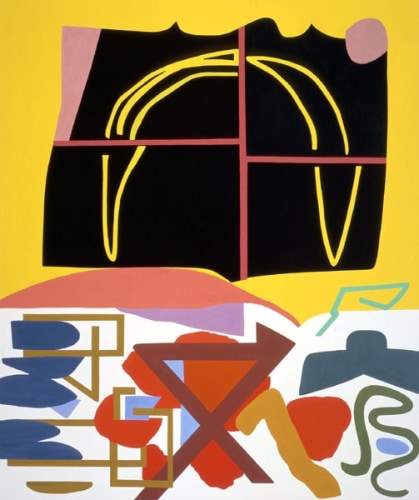

Shirley Jaffe

Four Squares Black

1993

oil on canvas

84 1/2 x 70 3/4 inches

Shirley Jaffe, an American painter working in Paris whose brilliantly colored, dancing geometric forms found an appreciative new audience when she began exhibiting in New York in the 1990s, died on Thursday in Louveciennes, France, near Versailles. She was 92.

Her death was confirmed by her brother, Jerry Sternstein.

Ms. Jaffe moved to Paris in 1949 and, somewhat to her own surprise, settled in and stayed. She was surrounded in the early days by a coterie of American artists, including Sam Francis, Joan Mitchell and Al Held, and the Canadian Jean-Paul Riopelle.

Her Abstract Expressionist work found a home in the Jean Fournier Gallery. She became a fixture on the scene. But she experienced a crisis in the early 1960s during a year in Berlin.

“I felt that my paintings were being read as landscapes,” she told Bomb magazine in 2004. “I became aware that gesture as gesture wasn’t sufficient for me. Something wasn’t working.”

Breaking with Abstract Expressionism, she embraced a highly individual, extremely refined geometric style that arranged single-color swirls, arabesques and hard-edged shapes in a tense, tingling formal arrangement, often against a white ground, that reminded critics of Matisse in his cutout phase, or Miró, or the American painter Stuart Davis. The color sense, and the joie de vivre, seemed profoundly French, the reckless energy American. She once described her canvases as “a general congestion of events.”

For the next half-century, working in a small apartment-studio on the Left Bank, Ms. Jaffe refined and extended her inquiries into the drama of form and color — always at a distance, literally and figuratively, from the currents of American art.

“After reinventing herself as a painter in the late 1960s she gradually, over the next 20 to 30 years, brought to her work an incredible vitality of form and complexity, not through gesture but through the very deliberate, patient shaping of form,” Raphael Rubinstein, the author of the 2014 monograph “Shirley Jaffe: Les Formes de la Dislocation” (“Shirley Jaffe: Forms of Dislocation”), said in an interview. “She arrived at this style through an internal developmental process. She was not part of a movement, so she was, in a sense, stylistically ahistorical. There was no other painter like Shirley.”

She was born Shirley Sternstein on Oct. 2, 1923, in Elizabeth, N.J. Her father, Benjamin, ran a shirt factory. After his death, when she was 10, the factory failed and her mother, the former Anna Levine, took her three children to the Brighton Beach neighborhood of Brooklyn.

After graduating from Abraham Lincoln High School, she earned a certificate in art from the Cooper Union in 1945. She then worked in the print department of the New York Public Library and for a time drew fashion sketches in the advertising department at Macy’s.

After marrying Irving Jaffe, she moved to Washington, where Mr. Jaffe was the White House correspondent for Agence France-Presse. She attended the Phillips Art School there before moving with her husband to Paris, where he continued working for the news agency and studied sociology at the Sorbonne on the G.I. Bill.

“I went to every contemporary gallery and looked at everybody’s work and gave myself a visual education,” Ms. Jaffe told Bomb. By the time she and her husband divorced in 1962, she had been given her first solo show in Bern, Switzerland, and found a place for herself in Paris’s small art community.

In the middle of the decade she began showing regularly at the Fournier Gallery, although Mr. Fournier was less than enthusiastic about the new direction her work had taken late in the decade.

“In the very first paintings it wasn’t geometry, more like ‘lite’ geometry,” she told the arts journal The Brooklyn Rail in 2010. “The lines weren’t always straight. I kept elements of a kind of gesture in a certain section of the painting. And then I began to develop on that.”

Reviewing her paintings at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in 2015 for The New York Times, Holland Cotter called her “an expressive geometrician” who “makes painting look like fastidiously worked joy.”

Ms. Jaffe’s fellow Abstract Expressionists regarded her break with gestural abstraction as heresy, and it was not until she was in her 60s that she was given her first solo show in New York, at the Holly Solomon Gallery. Tibor de Nagy Gallery has represented her in the United States since 2002. In France, she is represented by the Galerie Nathalie Obadia.

“She hasn’t played the crafty New York game of positioning oneself in other people’s opinions,” the critic Kay Larson wrote in New York magazine in 1990. “The paintings she has created are full of lonely nuance and exaltation, bracketed by a deep silence of mind and spirit.”

In 1999, the Musée d’Art Moderne de Céret, near the Spanish border, mounted a survey of her paintings of the previous two decades, and the 14th-century chapel of St. John the Evangelist in Perpignan, farther north, installed nine stained-glass windows that she had been commissioned to design.

She leaves no immediate survivors aside from her brother.

Ms. Jaffe worked steadily and methodically into her 90s, producing paintings and works on paper that showed no sign of flagging invention or vigor. The evidence was on display as recently as March, when Tibor de Nagy exhibited her mixed-media works on paper.

To the end, she retained the power to surprise. “I don’t believe that one thing follows from another, and I don’t want a logical reading in my painting,” she told Bomb. “I want the possibility of unpredictable change.”