There’s a subdued, muted irony to Ben Aronson’s new paintings (all 2010), the peculiar quiet before -- and after -- an explosion, not only literal but emotional. His Wall Street traders, matter of factly going about their business of making money, are haunted -- even taunted and stalked -- by death, implicit in the soldier with a gun in Volatility Index (2010), and more insidiously, in Aronson’s volatile handling. The policeman protects them, even as he conveys the violence done to Wall Street by terrorists -- and the violence the traders have done to Capitalism and America with their "speculations." They have betrayed both, suggesting the paradoxical meaning of the American flags on conspicuous display: Wall Street’s self-conscious patriotism masks its fiscal and social irresponsibility.

Intense and volatile, Aron’s painterliness bespeaks the intensity and volatility of the market, bringing its inner drama -- and anxiety -- to the surface. Sometimes the painterliness seems as free-wheeling as the supposedly free market, but it is as ingeniously "speculative" and "manipulative" as the market. It is a disruptive, uncanny painterliness, richly fluid and sometimes turbulent and angry, ingeniously undermining the scene and isolating the figures it ostensibly brings to life, even though they seem like mannequins ritualistically performing in a theater of the socially absurd. Aronson’s painterliness represents his critical consciousness even as it conveys his perceptual acuteness. It informs and takes over his scene the way the unconscious informs and takes over consciousness, which is one definition of madness: the quiet madness of money-making is his theme.

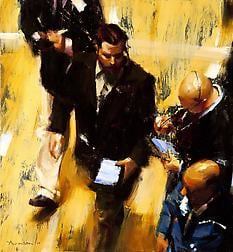

In Floor Traders, the sunshine yellow of the hyperactive painterliness usurps the space in which the men stand, dramatically contrasting with their dark suits. It is a symbolically loaded contrast, especially because it is expressively powerful: their dark suits suggest their dark deeds. Shadow informs their faces, suggesting that for all their business-like propriety they are sinister characters, however unwittingly. It is as though we are looking at a scene from a film noir -- a much more brilliantly nuanced and evocative scene than in any film. Sometimes Aronson’s painterliness seems to rough up his figures, almost blurring them into inconsequence, as in Risk and Reward. The dark figure becomes an extension of the luminous screens that surround him, and as peculiarly mechanical as they are. Indeed, the contrast of dispassionate technology and passionate art -- and photography and painting -- haunts Aronson’s works. In Talking Numbers, the painterliness all but consumes the figures, leaving us with peculiarly disembodied blackened fragments of flattened bodies. It is as though conflagration has hit the market -- there is a Sturm und Drang intensity to the painterliness -- leaving emotional as well as economic wreckage in its wake. Aronson’s modulated blackness is worthy of Velasquez and Manet. There is a tenebristic intensity to his painting, and also abstract expressionist energy.

Auction Fair Warning and Nighthawks, Delmonico’s -- an allusion to Hopper’s famous painting, and an ironical one, considering that Aronson’s figures are upper class and Hopper’s are lower class, and Delmonico’s is not exactly a night café -- seem less explosive and frantic, but the friction between the red and black that constructs their space is inflammatory, and the scenes are palpably tense, and emotional as well as fiscal risk and reward are at stake in them. The thin young girl seated between the two hungry fat-cats in Delmonico’s -- one is on his cell phone, still doing business even though night has fallen -- is probably a high-priced prostitute, and of course art is for sale to the highest bidder at an auction. Perhaps the two successful traders (after all, they can afford to eat at an expensive restaurant) are bidding for the girl, who is probably half as old as they are. The hunger for money and what it can buy -- art, sex, and above all power -- converge in Aronson’s masterpiece. Aronson’s traders are out to make a killing in more ways than one.

Whatever social narrative is conveyed by Aronson’s pictures, they are all exquisitely painted and emotionally haunting. Aronson is a social realist, like Hopper -- but he’s dealing with a different social reality -- but, unlike Hopper, he seems to be a critic of the social reality he depicts. Most of all he is a psychological realist: he has captured the mood of money in our messy economic and social times. Their morbid messiness is subsumed in the poignant spontaneity of Aronson’s painterliness, which is why his paintings will resonate beyond our times. His warm- and sometimes hot-blooded paintings transform his cold-blooded traders into deceptive illusions -- emblems of the grand illusion that is the American Dream and the Big Lie that is Wall Street -- making them memento mori of our times, yet another reason his paintings will survive them.

Ben Aronson, "Risk and Reward," Oct. 21-Nov. 27, 2010, at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, 724 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10019.

DONALD KUSPIT is distinguished professor of art history and philosophy at SUNY Stony Brook and A.D. White professor at large at Cornell University

Please follow the link below to view the review on the web:

http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/frontpage.asp